Executive Summary

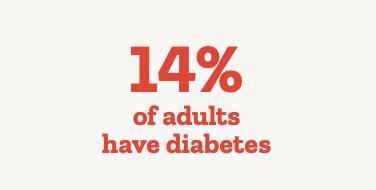

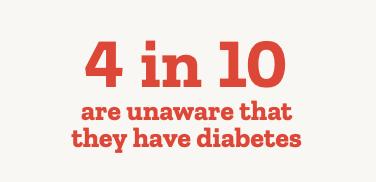

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic condition brought on by the body’s inability to produce sufficient amounts of insulin. The World Health Organization reports that in 2022, 14% of adults were living with diabetes.1 The number of people living with diabetes is probably much higher than the described prevalence, as many people only seek medical help after complications occur. The Diabetes Atlas projects that more than 4 in 10 people are unaware that they even have diabetes. They project that by 2050, approximately 853 million, or 1 in 8 adults, will be living with diabetes, a 46% increase from current levels.2

Diabetes management has several aspects to it, with areas of focus including education, meal planning, lifestyle changes and physical activity. When it comes to diabetes self-management, education plays an important role. Effective diabetes self- management education (DSME) can vastly improve outcomes for patients, as demonstrated by a review of various DSME programs.3 Group-based approaches to DSME have been championed for their ability to invite greater interactivity and interpersonal dynamics. They can foster certain educational activities such as social modelling or problem-based learning more effectively than in a one-on-one setting. Reviews of studies comparing group and individual models of DSME have identified that both offer substantial benefits, but group-based models tend to provide greater improvements in glycemic control, nutrition management and physical activity, blood pressure, patient satisfaction with their treatment and outcomes, and diabetes knowledge as a whole.4

There is also a growing body of literature focused on the need for healthcare professionals (HCPs) to address the emotional and psychological well-being of their diabetic patients. These inquiries identify a need for HCPs to regularly screen for both clinical and psychological metrics, and highlight the importance of building an honest rapport with patients. Addressing patients holistically—by understanding how their diabetes and their mental health issues can exacerbate each other—can help them self-manage more effectively.

Vita Valens was interested in implementing these two ideas of self-management education and holistic medical care in tandem, by devising a self-management education intervention that addressed the need for both group learning as well as holistic attention and instruction from an HCP. Over the course of the one-year intervention period, Vita Valens developed and implemented a program aimed at supporting health and wellness for New Yorkers living with diabetes. The aim was to enhance participants’ knowledge, encourage best practices in diabetes self-management, and strengthen individual self-efficacy for managing one’s own health. Vita Valens was concerned with implementing best practices from current research; thus, the two educational health living sessions hosted were designed as small group sessions of under 8 participants. The focus on small groups allowed participants to benefit from group learning, while limiting the participant pool size allowed participants to receive quality support from the medical practitioner conducting the seminar, with special emphasis on attending to the emotional and psychological needs of the attendees.

Background

Within the subject of diabetes management, the issue of addressing the emotional needs and well-being of the patient is not always highly prioritized by HCPs. A conference proceedings paper from the 6th International Diabetes Self-Management Alliance conference in 2023 indicates that, while the relationship between the patient and their HCP is vital to achieving positive self-management outcomes, HCPs spend a limited amount of time with patients, and express a lack of confidence in having emotional conversations with their patients.5 Most people report spending as little as 3-4 hours a year with their HCPs.6 Even though these interactions are rare, building a strong therapeutic alliance between the patient and the HCP through the ongoing management of the clinical and psychological aspects of the patient’s diabetes can embed shared decision making in their practice and help to ease the burden of diabetes.

The value of having HCPs address the emotional wellbeing of their diabetic patients is clearly understood, as seen from the American Diabetes Association’s extensive Diabetes and Emotional Health Workbook.7 This guide educates practitioners on a variety of topics ranging from Diabetes Distress (the emotional distress resulting from living with diabetes and the burden of relentless daily self-management) to more specific fears like the fear of hypoglycemia (the fear evoked by the risk and/or occurrence of low blood glucose levels). It also discusses psychological barriers to self-management including the reluctance to use insulin, as well as depression, anxiety, and eating disorders that can arise as a consequence of a diabetes diagnosis.

While the focus of Vita Valens’ intervention is not on the direct interaction between patients and their HCPs, the research conducted in this realm exemplifies the need for adequate psychological and psychosocial support for diabetic patients. Vita Valens was able to leverage these insights to develop intervention education curricula, and recruit a specialist to administer the interventions that would be sensitive to the emotional needs of participants as well in the delivery of self-management education.

Methodology

The intervention was available to all people within our sample subset with diabetes, pre-diabetes, or a member with family that they are caring for with diabetes. Individuals were contacted telephonically, invited to participate, and then enrolled in real time. The outreach and enrollment period took 3-4 weeks for each event. The first event was geared towards caregivers of a child or youth with diabetes or pre-diabetes. The second event was for individuals with diabetes or pre-diabetes.

The event and educational material content was shaped by our preliminary analysis and intervention goals, the most current research on DSME and emotional support for diabetes patients, best practices in the field, and feedback from prior educational initiatives. To increase access to the intervention we switched from in-person to virtual format and to reduce technological barriers to participation, we employed a commonly used technology, Zoom, to host the online educational events. By offering these events virtually, we also aimed to broaden our reach across geographic regions, including underserved areas where access to diabetes education may be limited.

Several best practices were identified in the design and implementation of this intervention. The selected clinician who led the intervention sessions had comprehensive experience in developing and administering diabetes education, as well as specific experience working with pediatric patients and their families. The educational materials were developed in collaboration with the clinician to address topics including nutrition and physical activity. Each of the two sessions were 1.5-2 hours long, to ensure that adequate time was dedicated to instructional education as well as group discussion and direct reinforcement. The events were in the evening after regular business hours to make it more convenient for participants. Throughout the intervention period, we continued to monitor and adjust the intervention in response to the needs and preferences of the participants.

The evaluation of the diabetes education events utilizes a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative data from participation information and post-event surveys with qualitative feedback from open-ended responses. Outreach, enrollment, attendance, and participation were tracked through call records and maintaining an attendance roster for each event. Surveys and feedback were collected telephonically for all participants following each event. The focus of this paper is on the qualitative feedback provided by participants to evaluate the level of support and education they felt that they received.

Findings and Discussion

Across the two events, a total of ten individuals participated. The qualitative measures utilized were chosen to provide a comprehensive understanding of the intervention and the perceived impact by the participants. Due to the short intervention period and small sample size, success was determined by the successful implementation of the program and impact was assessed through qualitative self-reported results and feedback.

Three attempts were made to reach each member telephonically to maximize the response rate. Qualitative data was collected during and after the wellness group sessions. The members all reported positive experiences during and after the events. Many expressed feeling grateful for the attention and time to ask questions. Others found the group format to be very supportive and encouraging. Participants shared resources for helping choose healthy food while at the grocery store, validated others’ experiences and provided suggestions for navigating challenges such as the high cost of healthy food and offered ideas for doable diet and lifestyle changes. There was a strong sense of support in discussing medications. Many participants found the medication side effects challenging, and positively responded to the facilitator’s communication style in conveying empathy for their circumstances. The participants shared and contributed openly, asked many questions, and provided personal experiences, which the facilitator was able to validate. The group format showed to be a very positive component of the intervention.

The small sample size impacts the generalizability of the findings beyond the sample group and limits our ability to draw conclusions from the intervention results. Given the sample size there is insufficient statistical power to detect significant effects or relationships within the received feedback. We analyzed the intervention primarily through descriptive statistics and complemented this with informal qualitative data collected throughout the intervention.

Conclusion

Participants provided rich qualitative feedback indicating high levels of engagement and satisfaction. Many reported that the sessions felt meaningful, informative, and there was notable appreciation for the opportunity to learn from and ask questions of a clinician with significant experience in endocrinology disorders and a compassionate disposition to their circumstances. Many expressed interest in attending future sessions, even on different health topics.

These findings highlight the importance of community-based educational events, particularly those that are data-informed, accessible, and approach patient education and care from a holistic perspective. Even with a small sample size, strong participant engagement and positive reception point to the potential impact of these interventions when implemented thoughtfully. Future efforts may benefit from offering sessions at varied times and sustaining community engagement over time.

Citations

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes

Ernawati U, Wihastuti TA, Utami YW. Effectiveness of Diabetes Self-Management Education (DSME) in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2Dm) Patients: Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Public Health Research. 2021;10(2). doi: 10.4081/jphr.2021.2240

Tricia S. Tang, Martha M. Funnell, Robert M. Anderson; Group Education Strategies for Diabetes Self-Management. Diabetes Spectr 1 April 2006; 19 (2): 99–105. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaspect.19.2.99

Hadjiconstantinou, M., Causer, H., Graham, R., Kelleher, S. and Davies, M. (2023), Reflections on the Diabetes Self-Management Alliance Workshop: providing better emotional support in diabetes routine care. Pract Diab, 40: 39-42. https://doi.org/10.1002/pdi.2487

Shubrook JH, et al. Time needed for diabetes self-care: Nationwide survey of certified diabetes educators. Diabetes Spectr 2018; 31(3): 267–71.

https://professional.diabetes.org/professional-development/behavioral-men-tal-health/MentalHealthWorkbook

Fisher L, Mullan JT, Skaff MM, et al. Predicting diabetes distress in patients with type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal study. Diabet Med 2009; 26: 622–7. doi:10.1111/j.1464-491.2009.02730.x

Goldney RD, Phillips PJ, Fisher LJ, et al. Diabetes, depression, and quality of life: a population study. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1066–70. doi:10.2337/diacare.27.5.1066

Hutter N, Schnurr A, Baumeister H. Healthcare costs in patients with diabetes melli-tus and comorbid mental disorders–a systematic review. Diabetologia 2010;53:2470–9. doi:10.1007/s00125-010-1873-y

Gilmer TP, O’Connor PJ, Rush WA, et al. Predictors of health care costs in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2005;28:59–64. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.1.59

McMorrow R, Hunter B, Hendrieckx C, et al, Effect of routinely assessing and address- ing depression and diabetes distress using patient-reported outcome measures in improving outcomes among adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review proto- col, BMJ Open 2021;11:e044888. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044888

Dawson J, Doll H, Fitzpatrick R, et al. The routine use of patient reported outcome measures in healthcare settings. BMJ 2010;340:c186. doi:10.1136/bmj.c186

Nicolucci A, Kovacs Burns K, Holt RIG, et al. Diabetes attitudes, wishes and needs sec- ond study (DAWN2™): cross-national benchmarking of diabetes-related psychosocial outcomes for people with diabetes. Diabet Med 2013;30:767–77.doi:10.1111/dme.12245